Robustness versus acceleration

My blog post on the Zen of Gradient Descent hit the front page of Hacker News the other day. I don't know how that happened. It got me more views in one day than this most humble blog usually gets in half a year. I thought I should take this as an excuse to extend the post a bit by elaborating on one remark I made only in passing. You don't need to go back to reading that post unless you want to. This one will be self contained.

The point I made is that basic Gradient Descent (GD) is noise tolerant in a way that Accelerated Gradient Descent (AGD) is not. That is to say, if we don't have exact but rather approximate gradient information, GD might very well outperform AGD even though its convergence rate is worse in the exact setting. The truth is I was sort of bluffing. I didn't actually have a proof of a formal statement that would nail down this point in a compelling way. It was more of a gut feeling based on some simple observations.

To break the suspense, I still haven't proved the statement I vaguely thought was true back then, but fortunately somebody else had already done that. This is a thought provoking paper by Devolder, Glineur and Nesterov (DGN). Thanks to Cristobal Guzman for pointing me to this paper. Roughly, what they show is that any method that converges faster than the basic gradient descent method must accumulate errors linearly with the number of iterations. Hence, in various noisy settings auch as are common in applications acceleration may not help---in fact, it can actually make things worse!

I'll make this statement more formal below, but let me first explain why I love this result. There is a tendency in algorithm design to optimize computational efficiency first, second and third and then maybe think about some other stuff as sort of an add-on constraint. We generally tend to equate faster with better. The reason why this is not a great methodology is that sometimes acceleration is mutually exclusive with other fundamental design goals. A theory that focuses primarily on speedups without discussing trade-offs with robustness misses a pretty important point.

When acceleration is good

Let's build some intuition for the result I mentioned before we go into formal details. Consider my favorite example of minimizing a smooth convex function \({f\colon \mathbb{R}^n\rightarrow\mathbb{R}}\) defined as

\(\displaystyle f(x) = \frac 12 x^T L x - b^T x \)

for some positive semidefinite \({n\times n}\) matrix \({L}\) and a vector \({b\in\mathbb{R}^n.}\) Recall that the gradient is \({\nabla f(x)=Lx-b.}\) An illustrative example is the Laplacian of a cycle graph:

\(\displaystyle L = \left[ \begin{array}{ccccccc} 2 & -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & \cdots & -1 \\ -1 & 2 & -1 & 0 & 0 & \cdots & 0 \\ 0 & -1 & 2 & -1& 0 & \cdots & 0 \\ \vdots & & & & & & \end{array} \right] \)

Since \({L}\) is positive semidefinite like any graph Laplacian, the function \({f}\) is convex. The operator norm of \({L}\) is bounded by~\({4}\) and so we have that for all \({x,y\in\mathbb{R}^n:}\)

\(\displaystyle \|\nabla f(x) -\nabla f(y)\| \le \|L\|\cdot\|x-y\|\le 4 \|x-y\|. \)

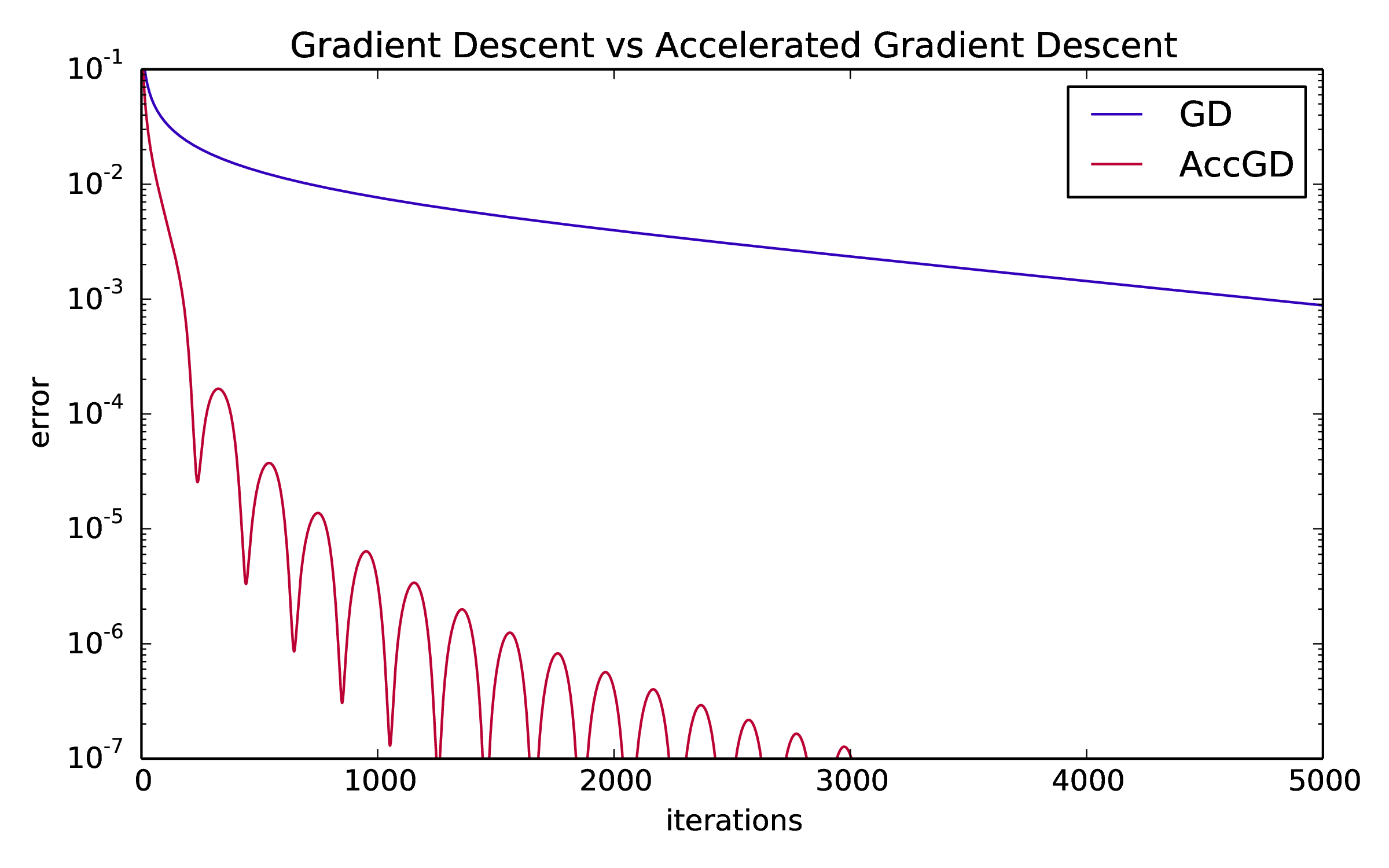

This means the function is also smooth and we can apply AGD/GD with a suitable step size. Comparing AGD and GD on this instance with \({n=100}\), we get the following picture:

It looks like AGD is the clear winner. GD is pretty slow and takes a few thousand iterations to decrease the error by an order of magnitude.

When acceleration is bad

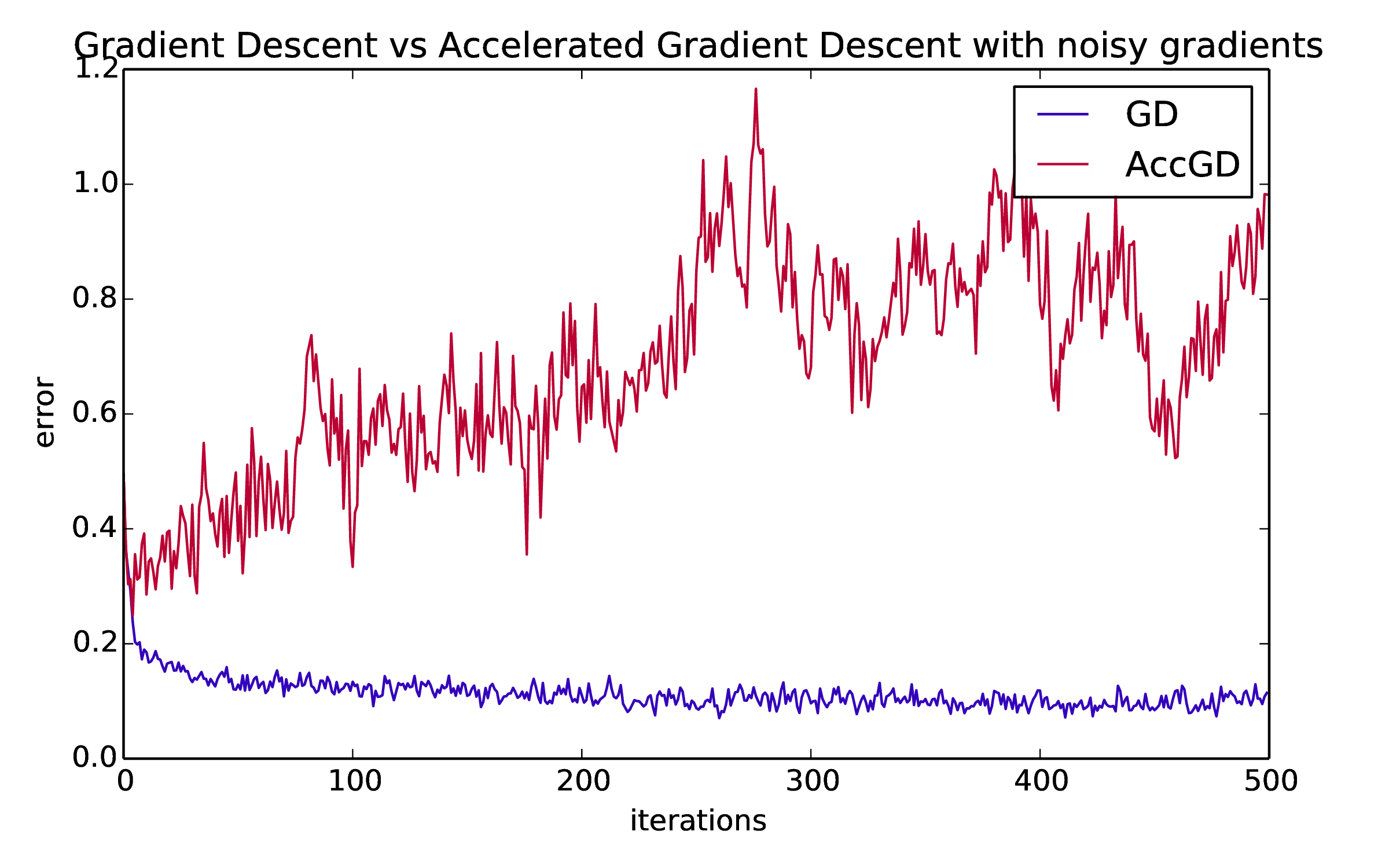

The situation changes dramatically in the presence of noise. Let's repeat the exact same experiment but now instead of observing \({\nabla f(x)}\) for any given \({x,}\) we can only see \({\nabla f(x) + \xi}\) where \({\xi}\) is sampled from the \({n}\)-dimensional normal distribution \({N(0,\sigma^2)^n.}\) Choosing \({\sigma=0.1}\) we get the following picture:

Gradient descent pretty quickly converges to essentially the best result that we can hope for given the noisy gradients. In contrast, AGD goes totally nuts. It doesn't converge at all and it adds up errors in sort of linear fashion. In this world, GD is the clear winner.

A precise trade-off

The first thing DGN do in their paper is to define a general notion of inexact first order oracle. Let's recall what an exact first-order oracle does for an (unconstrained) convex function \({f\colon\mathbb{R}^n\rightarrow \mathbb{R}}\) with smoothness parameter \({L.}\) Given any point \({x\in\mathbb{R}^n}\) an exact first order oracle returns a pair \({(f_L(x),g_L(x))\in\mathbb{R}\times\mathbb{R}^n}\) so that for all \({y\in\mathbb{R}^n}\) we have

\(\displaystyle 0\le f(y) - \big(f_L(x) + \langle g_L(x),y-x\rangle\big)\le \frac L2\|y-x\|^2\,. \)

Pictorially, at every point \({x}\) the function can be sandwiched between a tangent linear function specified by \({(f_L(x),g_L(x))}\) and a parabola. The pair \({(f(x),\nabla f(x))}\) satisfies this constraint as the first inequality follows from convexity and the second from the smoothness condition. In fact, this pair is the only pair that satisfies these conditions. My slightly cumbersome way of desribing a first-order oracle was only so that we may now easily generalize it to an inexact first-order oracle. Specifically, an inexact oracle returns for any given point \({x\in\mathbb{R}^n}\) a pair \({(f_{\delta,L}(x),g_{\delta,L}(x))\in\mathbb{R}\times\mathbb{R}^n}\) so that for all \({y\in\mathbb{R}^n}\) we have

\(\displaystyle 0\le f(y) - \big(f_{\delta,L}(x) + \langle g_{\delta,L}(x),y-x\rangle\big)\le \frac L2\|y-x\|^2+\delta\,. \)

It's the same picture as before except now there's some \({\delta}\) slack between the linear approximation and the parabola.

With this notion at hand, what DGN show is that given access to \({\delta}\)-inexact first-order oracle Gradient Descent spits out a point \({x^t}\) after \({t}\) steps so that

\(\displaystyle f(x^t) - \min_x f(x) \le O\big(L/t\big) + \delta\,. \)

The big-oh notation is hiding the squared distance between the optimum and the starting point. Accelerated Gradient Descent on the other hand gives you

\(\displaystyle f(x^t) - \min_x f(x) \le O\big(L/t^2\big) + O\big(t \delta\big)\,. \)

Moreover, you cannot improve this-tradeoff between acceleration and error accumulation. That is any method that converges as \({1/t^2}\) must accumulate errors as \({t\delta.}\)

Open questions

- The lower bound I just mentioned in the previous paragraph stems from the fact that an inexact first-order oracle can embed non-smooth optimization problems for which a speedup is not possible. This is interesting, but it doesn't resolve, for example, the question of whether there could be a speedup in the simple gaussian noise addition model that I mentioned above. This isn't even a toy model---as you might object---since gaussian noise addition is what you would do to make gradient descent privacy preserving. See for example an upcoming FOCS paper by Bassily, Smith, Thakurta for an analysis of gradient descent with gaussian noise.

- Is there an analog of the DGN result in the eigenvalue world? More formally, can we show that any Krylov subspace method that converges asymptotically faster than the power method must accumulate errors?

- The cycle example above is often used to show that any blackbox gradient method requires at least \({t\ge \Omega(1/\sqrt{\epsilon})}\) steps to converge to error \({\epsilon}\) provided that \({t}\) is less than the number of vertices of the cycle, that is the dimension \({n}\) of the domain. (See, for example, Theorem 3.9. in Sebastien Bubeck's book.) Are there any lower bounds that hold for \({t\gg n}\)?

Pointers:

The code for these examples is available here.

To stay on top of future posts, subscribe to the RSS feed or follow me on Twitter.